CMOs get no respect. They have a lot of expectations placed on them—sometimes even quota—but marketers have no credibility with CEOs (“73% of CEOs say marketers lack credibility”, Lara O’Reilly, Marketing Week, June 2011), and marketing doesn’t have the board’s ear either (“Why CEOs Can’t Blame Marketing or Sales for Lack of Alignment”, Christine Crandell, Forbes, February 2011).

Both articles claim different reasons for the lack of respect. Lara O’Reilly cites a study by Fournaise that makes very good points why the CMO is at fault, and Christine Crandell opines eloquently why the CEO is to blame for the lack of respect the CMO gets.

The general complaint is that marketers cannot prove with certainty how much impact their efforts have on the top-line of the business (my opinion: because marketing is a process that takes time, and it’s difficult to measure any network effect with precision).

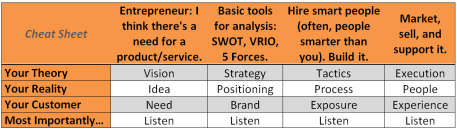

Jerome Fontaine, CEO and chief tracker of Fournaise, says that “. . . marketers [need to] start speaking the P&L language of their CEOs. . .” CEOs want CMOs to have a greater grasp of the business, not just the pretty side of relationship building. CEOs want to know about “revenue, sales, EBIT and market valuation.”

Market-Based Management: Strategies for Growing Customer Value and Profitability (Pearson Prentice Hall, Fifth Edition, 2009)—a fantastic book for anyone who needs to grasp the basic concept that marketing is a lot more than promotion and advertising—offers a simple formula to show what incremental revenues marketing produces:

Net Marketing Contribution, Roger-Best, ©2009 Pearson Prentice Hall

McKinsey even published a whole article on “Measuring marketing’s worth” (see previous post). The article tries to teach the CEO how to appreciate the CMO. Instead, in my opinion, the article is actually an excellent blueprint to help aspiring CMOs prepare for their larger role. Still, ROI does little to convince the CEO that the CMO is moving the needle in an appreciable fashion.

The more serious problem appears to be that the two sides do not understand one another. The CEO doesn’t understand marketing beyond promotion and advertising. The CMO doesn’t understand accounting and finance. Two ships passing in the night.

Let’s have a brief look at both positions.

CEOs are captains of the ship. They must have an understanding of every core discipline in the company, even if they themselves cannot be expert at everything. That’s why they hire very smart people to do the things they themselves don’t have the time or knowhow to do well consistently. CEOs are also the face of the company, and in some ways must embody the brand. They must be super-smart brand ambassadors in both B2B and B2C settings.

The CEO is responsible for:

- Corporate performance—profitability and valuation.

- Corporate strategy—assuring that the company remains a successful going concern.

- Capitalization—so that the company can reinvest in growth and innovation.

- Corporate culture—creating the desired climate and leading by example.

- The C-Suite—recruiting the best executive talent so that the company outperforms.

- Executive performance—understanding the correct performance metrics (Christine Crandell’s point).

CMOs are brand-builders who craft unique and powerful value propositions. If all they think themselves responsible for is lead generation, then they are only advertisers. CMOs must want to influence innovation (through voice of the customer and competitive positioning), and lead sales, marketing, and customer care. You read correctly; I believe the marketing department must own the customer (customer lifecycle management). Sales, promotion, advertising, and customer care are all functions of marketing; marketing being the discipline of bringing a product into the market successfully. And a sale is not successful unless the customer is happy long-term.

The CMO is responsible for:

- Competitive strategy—being one step ahead of direct competitors, new entrants, and substitutes.

- Branding/positioning—placing irresistible core values in the buyer’s mind.

- The customer—lifetime customer satisfaction and perceived value.

- Pricing—for the greatest lifetime profit and customer retention (not volume-based).

- Corporate image—the public perception of the company.

- Lead generation—meaningful and authentic message dissemination that moves markets.

So apparently there is little overlap between the CEO’s and CMO’s responsibilities. Crazy, since they are co-pilots for success.

Back to the Fournaise study. Revenues, sales, and EBIT are accounting principles. Valuation is a finance principle.

Basic accounting principles are easily learned. I bet there’s a good Dummies-book out there. Now it finally dawns on us: we marketers are hated by everyone in the company who values a balance sheet. Marketing, the entire department—overhead and all marketing activities—is an expense. No wonder there is such a myopic focus on ROI and lead generation. CMOs must perform by the fiscal year calendar, which pretty much kills any long-term strategic and tactical initiatives around building a brand.

The only time marketing expenses are “good” is when they create a total corporate loss that the company can then write off in subsequent periods. That in itself is an untenable situation.

Accountants lord over the marketing department, however subtly.

To win real respect, CMO’s must increase the value of the company beyond the sum of its future earnings. Good ones do, but few of them know how to prove it. And that’s the real rub: CEOs and accountants want CMOs to prove something that they’re not permitted to prove by accounting standards.

Goodwill—what I call the toilet bowl of the balance sheet, because it’s essentially a bunch of hooey—does not permit for the accounting of internally created value (read: brands). Only acquired brands can be accounted for on the balance sheet under goodwill. That math is actually very simple: brand value is the difference between the book value of a company, and what it was actually acquired for. And that’s the needle (read: multiple) that the CMO has to move.

Which needle? The valuation needle.

So, don’t get another MBA, this time in finance. Learn about valuation via an adult-ed course at your local community college or take an online course. Even a simple search for “company valuation” on Investopedia brings up great results.

These are not tricky concepts, but they do take time to acquire as skills. The best thing you can do is practice for a little while, and then begin to build a valuation model for your company that you test over time, and that shows how you are moving the needle (or could be moving the needle given permission).

Give it some months, then you spring it on your boss and. . .*BAM*:

- Instant credibility with the CEO and the board.

- Bigger budget!

- Permission for long-term strategic planning and tactical execution.

- Increased self-worth (and probably pay if you negotiate well at the close of the fiscal year).

And now for the real conclusion: career advancement is not the real benefit here.

There are many different valuation models, and valuation, for the most part, is a bunch of hooey, too. It’s like selling your home, which is worth only what someone else is willing to pay for it, not what you think it is worth. The book value of your home is the worth of the land and the dwelling on it—at cost. That’s what you pay taxes on. But you know that there’s additional value in the place. And that value is determined by many factors: listing price of comparable dwellings, ranking of school district, quality of home construction, proximity to emergency services, etc. These and other factors give your home value beyond book.

The better prepared you are for your buyer—the better you can support your arguments in your valuation model—the more likely you can affect a positive outcome for yourself. That’s because valuation teaches you to examine where and how marketing adds value to the company. And when you understand that, you also market better.

And that’s how you build a brand, by listening to the market and understanding how to respond. Your model will tell you what to pay attention to. What are brands? They are needle-movers; they get chosen more frequently, even at higher prices. You can be a needle-mover, too.

[And thus finance quietly trumps accounting. But don’t tell the accountants.]